Later on, the media distilled my generation of San Francisco-bred, disaffiliated young people into a mess of love beads, LSD and free sex in Golden Gate Park. It wasn’t like that, not at all. This installment concludes the story of a student co-op in San Francisco’s Fillmore District in the years 1962-64, told in the words of three survivors, Gerald Keil, Loren Means, and Nathan Zakheim.

Later on, the media distilled my generation of San Francisco-bred, disaffiliated young people into a mess of love beads, LSD and free sex in Golden Gate Park. It wasn’t like that, not at all. This installment concludes the story of a student co-op in San Francisco’s Fillmore District in the years 1962-64, told in the words of three survivors, Gerald Keil, Loren Means, and Nathan Zakheim.

To begin at Part 1, click here.

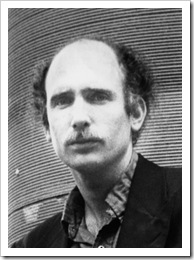

Nathan Zakheim

LOREN MEANS: Nathan Zakheim’s father, Bernard Baruch Zakheim, was a painter, muralist, and sculptor who had been a peer of Marc Chagall in Germany and a collaborator with Diego Rivera in the US and Mexico, working on murals at Coit Tower and UC Medical Center. Nathan’s mother, Phyllis, was the last of the line of a family that had come to America shortly after the Mayflower and had owned a large portion of downtown Santa Barbara and Montecito. According to Nathan, they introduced oranges and bananas to southern California. She and Bernard had met when she was researching his UC Med Center mural, which had been wallpapered over by on the order of a professor who considered the murals a distraction to his students.

Nathan stomped around with a full beard and a sheepskin vest, with a guitar strapped to his back. I heard Nathan say to my girlfriend Kit, “Aren’t you even partly Jewish? How do you stand it?” He worked in a kosher delicatessen in the Fillmore District, and at one point he offered me some wizened lamb chop from his backpack. I ate what I could of it, but when I tried to throw away the bone, he snatched it from me and ate some more of it. “Mr. Means,” he said, “you eat like a millionaire.”

GERALD KEIL: Nathan became the backbone of our domestic community.  He knew the best places to shop cheaply, and brought home quantities of chicken backs and bacon ends which cost us practically nothing. Chicken backs could be reduced to gelatin for soups and sauces. Bacon ends were considered industrial waste, but were far more substantial than those pricey strips of bacon which were mostly fat – a befitting token of the society from whose irrational consuming habits we profited.

He knew the best places to shop cheaply, and brought home quantities of chicken backs and bacon ends which cost us practically nothing. Chicken backs could be reduced to gelatin for soups and sauces. Bacon ends were considered industrial waste, but were far more substantial than those pricey strips of bacon which were mostly fat – a befitting token of the society from whose irrational consuming habits we profited.

NATHAN ZAKHEIM: From my father, I learned how to find food with no commercial value but huge flavor value: chicken backs to make soup, and fish heads to make chowder. The fish heads were full of gelatin, and were actually tastier and more nutritious than the sought after fillets of the fish.

At the time, I was driving a delivery truck all over the city, so I had prime opportunity to find bargains. I would spend a few minutes each in about ten shops per day. Each shop had a super special to lead in shoppers, so I would only buy that bargain and nothing else. Or I would take my 1945 military issue Harley Davidson down to the Farmer’s Market on Alemany Blvd, and load up duffel bags with produce, bargaining fanatically with the farmers, and getting super low prices. Then I would load as much as I could on the back of the ‘cycle, and put a huge duffel bag over the handle bars, where it protruded as I rode home on the Skyway at 60 mph or more, in a manner I can only describe as phallic.

Or I would take my 1945 military issue Harley Davidson down to the Farmer’s Market on Alemany Blvd, and load up duffel bags with produce, bargaining fanatically with the farmers, and getting super low prices. Then I would load as much as I could on the back of the ‘cycle, and put a huge duffel bag over the handle bars, where it protruded as I rode home on the Skyway at 60 mph or more, in a manner I can only describe as phallic.

GERALD: But Nathan’s greatest revelation was kasha – whole-grained buckwheat. Nathan, who, despite the bacon ends, was a self-professed Ashkenazi, explained that the Polish army marched on kasha, which contained more protein than any other cereal; and since meat was a rare commodity for us, we ate kasha with eggs and bacon ends mornings, and in the evening, kasha with vegetables, especially onions, and the occasional meat scraps. Takes getting used to, but I came to like it. I still make a kasha dish every once in a while, and each time I do I picture Nathan, with his dark brown curly locks and ample full beard, looking as if he had just arrived fresh from the shtetl.

GERALD: But Nathan’s greatest revelation was kasha – whole-grained buckwheat. Nathan, who, despite the bacon ends, was a self-professed Ashkenazi, explained that the Polish army marched on kasha, which contained more protein than any other cereal; and since meat was a rare commodity for us, we ate kasha with eggs and bacon ends mornings, and in the evening, kasha with vegetables, especially onions, and the occasional meat scraps. Takes getting used to, but I came to like it. I still make a kasha dish every once in a while, and each time I do I picture Nathan, with his dark brown curly locks and ample full beard, looking as if he had just arrived fresh from the shtetl.

NATHAN: I wanted to experiment with a notion that we could live communally, sharing all food and communally purchased items. We created the idea of purchasing separately, cooking communally, and then dividing the receipts later and paying up until everyone had paid the same amount. My father was an avowed Marxist, and idealized the idea of "From each according to his ability, and to each according to his need." I had a burning desire for this "communism experiment" to actually occur among a likely group of SF State students who had much to gain and little to lose by such an experiment.

GERALD: All in all, we lived cheaply. We pooled expenses, and receipts for everything landed in a cardboard box. I distinctly remember, at the end of one six-week period, we opened the box, checked the balance, and discovered that we had only paid out some $35.00 in all.

NATHAN: My mother, who was a genius at frugality, was horrified that we were living on twelve dollars per month. She cried out with motherly outrage, "You should be spending twelve dollars per WEEK!” My mother knew how to stretch dollars in ways that truly boggled the mind. She could not imagine that I, in San Francisco, was able to find ultra-bargains and wholesale items that, when bought in bulk, were practically non-existent in cost per person.

GERALD: The final member of our community was Rodney Albin. He must have joined us around June 1963, after the close of the Spring semester. At that time I had a job downtown, and when I returned one evening, there was Rodney, fully installed. His room was full to overflowing. The most conspicuous item was a huge, self-made harpsichord which straddled the bed so only its upper half was free. This was a space-saving measure, since Rodney’s room, like the others in the corridor, would have otherwise been too small to accommodate both bed and harpsichord. At the foot of this bed-harpsichord arrangement was a chest of drawers, and strewed around the room were string instruments of all sorts, and piles of books. Rodney was not the orderly sort.

It was a unique scene; this oversized harpsichord with a geared tuning peg on each string, and Rodney, sitting upright in bed, legs stretched out beneath the harpsichord, apparently exhausted from the effort of moving all his stuff, quietly frailing a banjo. He was even thinner than I was, and pale as a Norwegian in mid-winter. He looked to be in his early twenties, yet his hair was already thinning, accentuating a high round forehead which contrasted with his meager, somewhat sunken cheeks. His mustache was not immediately evident in the pallid light, even though he wore it untrimmed, since his hair was almost skin-colored. But what most caught my attention was his gaze: warm, kind, good-natured, submerged in music, at perfect ease despite all these new faces around him.

It wasn’t long – a few days at most – before Nathan took the initiative and brought a degree of order into Rodney’s domain. Using planks and bricks from somewhere, Nathan fashioned bookshelves which stretched from just inside the door down to the end of the corridor wall, continuing at right angles along the adjoining wall almost to the corner of Rodney’s bed. Nathan took great pride in the fact that the bookshelves were of cantilever construction, the plank ends hanging free in the air. From now on, Rodney had a modicum of order and a maximum of cantilever.

In the course of time Rodney taught me fingerpicking – both bluegrass and frailing. I had my father’s plectrum banjo with me, but with its four strings it wasn’t suited for fingerpicking. Rather than permanently altering Dad’s instrument, I fashioned a wooden add-on held in place by the combined force of the tightened G string and a specially fashioned clip.. Rodney contributed by installing a banjo tuning peg. The contraption worked like a charm; and, through building it, we discovered a mutual and lasting affinity.

Rodney and I had complementary talents: he could pick anything which had strings, and I could blow just about anything which had holes in it. In time I picked up enough banjo technique to make an agreeable noise, but I never even remotely approached the proficiency of Rodney Kent Albin.

Late 1967. Rodney and Ponderpig on boat somewhere in space.

Late 1967. Rodney and Ponderpig on boat somewhere in space.

In the early summer of 1964, Big Dave, the owner of 857 Divisadero St., decided to remodel his property. He gave his tenants thirty days notice. Rodney Albin paid a visit to his uncle, Henry Arian, whose company had just purchased a Victorian mansion at the corner of Page and Broderick Streets. It had most recently been used as a boarding house for Irish immigrants. Arian needed time to arrange financing to pull it down and replace it with new Redevelopment units, and Rodney made him an offer, "Rent it to me, and I will sublet the rooms to San Francisco State students. You won’t have a thing to worry about." They settled on $600 a month rent. And thus was born the most famous hippie rooming house in the world, 1090 Page Street.

The End of 857 Divisadero

NATHAN: I was the last tenant in 857 Divisadero St. I had fallen ill with a very bad case of flu after everyone else moved out, and I remained in my room unable to move. The owner had already turned off the power, water and gas. Since I was unable to leave, I had to make a temporary light by pouring cooking oil into a bowl and draping pieces of sweatshirt over the edge as wicks to make an oil lamp. The only water in the building was in the toilet tank, so that was all I had to drink while judiciously resisting the temptation to flush the toilet. I remember a basically hallucinatory Rodney Albin looking in my door at my comatose body and asking me , "Are you going to be all right"? before closing the door and leaving for the last time. He did not realize that I was that sick, and I was too sick to be able to communicate it to him!

GERALD: I departed 857 Divisadero at the beginning of December, 1963 to study abroad. Upon my return from Europe at the end of August, 1964 I learned that everyone had moved to 1090 Page Street, and I followed, sharing the front room with Rodney until getting married in mid-1965.

We were a highly divergent configuration of individuals, each with his own particular interests, yet, as a group, harmonious. With the exception of the rifle incident with Edmund, I can’t remember a cross word being spoken. We were certainly Bohemians, but essentially that just means being poor, young and literate. We didn’t really fit the labels of the time – neither Beatnik nor Hippie. You might say we were post-Beatniks and pre-Hippies – image-neutral, sporting the mannerisms and wearing the uniforms of neither.

LOREN: We were a transitional group, between the conformity of the ’50s and a different kind of conformity in the ’60s, and we didn’t fit into either. I came to San Francisco for the Beat movement, but it had been replaced by Carol Doda and topless dancing. I lived in the Haight-Ashbury during the Hippie era, and one of my roommates was an organizer of the San Francisco State student strike. I was friends with the founders of the Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother and the Holding Company, and with filmmakers who did light shows, but I wasn’t interested in any of that. Buck Moon once told me that I was in the midst of all the movements in San Francisco, but not a participant in any of them.

But in the late ’60s, a concept of “underground” expression emerged in San Francisco that I did identify with and participate in. The avant-garde art, science, and culture scene in San Francisco has grown to outshine even New York and London. When we started making avant-garde art in the ’60s and ’70s, there was no tradition for us to emulate. Now those of us who are still manifesting this expression are the tradition, and younger people joining us are participating in that expression. I recently played a concert where the age range was from 75 to early 20s, and we all celebrated the unique cultural environment that the San Francisco Bay Area has become.

PONDERPIG: As I walked around the City in those days. I met interesting guys like Loren and Gerry and Nathan and Rodney. I also met freaks and potheads, poets and folkies, Fidelistas and mystics, junkies, conscientious objectors, meth freaks, super-8 filmmakers, actors, painters and assorted crazies. But I never met one person who came to San Francisco to join the hippies. Man or woman, boy or girl, the people I met were pursuing their boho destiny on their own terms. As Gerald says, they were a ‘divergent configuration’ tied together by some unspoken fraternal force. Maybe we felt the turning and turning in the widening gyre, the blood-dimmed tide unloosed and the earth quaking already beneath us.

Or maybe not. Maybe we just preferred strolling along, a bit out of step with the straight world busy marching somewhere we didn’t want to go. It was our preference. We gave each other permission to be different in any damn way we pleased. And that, my friends, is the quality (along with psychedelic drugs) that led to the flowering of the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco in 1966.

NOTE: The next chapter in the ongoing story can be found here: Luminaries of the Haight #4: 1090 Page Street. More on Rodney Albin may be found here: Luminaries of the Haight-Ashbury: Rodney Albin.

Vintage San Francisco photos: SAN FRANCISCO HISTORY CENTER, SAN FRANCISCO PUBLIC LIBRARY.

“…the turning and turning in the widening gyre, the blood-dimmed tide unloosed and the earth quaking already beneath us.”

LikeLike

Man, I love those words and I didn’t want my meager comment to be in the same area. Thay’s why I posted separately. Beautiful end to what was just the beginning. Keep writing, Brer Pig!

LikeLike

Thanks,Leo. But, much as I would like to, I can’t take credit for them. With some slight alterations, the words were written by William Butler Yeats in his most remarkable and relevant poem, The Second Coming

LikeLike

Well, it’s a good thing you ‘fessed up. Otherwise you’d be a big-time plagarist. Don’t take advantage of my young guy naivete. I don’t know all them French expressionist existential poets like you old beats do.

“Though I’d my finger on my lip,

What could I but take up the song?

And running crowd and gaudy ship

Cried out the whole night long…”

LikeLike

Yeats is the second best poet of all time. And I’m not sure who the best poet is.

LikeLike

Speaking of Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Joanie Didion penned some interesting and witty remarks on the late 60’s San Francisco scene–though rather critical, cynical, and probably not copacetic-enough for the Pig crew.

There was one old show at Winterland (I’ve seen the poster) I wish’d to have experienced (though way before my time): the Grateful Dead with Zappa and the Mothers. Whoa-nicity. Groovy SF hippie-granola vs. southside motorhead jazz/freak-rock/doo wop (I’d have to say FZ & MoI…. won).

(Who, or what exactly is the Rough Beast of Billy Yeats’ ditty, however, P-P? Proposed candidates: capitalist imperialism. religious fundamentalism. Lady Gaga)

LikeLike

We of the Pig crew reject Joan Didion’s calumnies with derision and scorn. She was a terminally depressed person who saw evil where there were only sad children come to wear flowers in their hair. It wasn’t their fault they got it wrong. They had no depth, they had to learn. Do you remember what she wrote about Peter Berg? She made him sound like Mephistopheles. The guy was trying to bring reality into the hippie vision. He went on to an admirable career as an environmental radical, one of the first. A link to his website: http://www.planetdrum.org/

LikeLike

Not really–do recall the Doors essay and the one on the Haight (maybe that had Berg in it), a few others. I agree she’s sort of dull, neurotic, maybe even….a snitch (I think Stone portrayed her as such in the Doors flick), but she wielded fairly

tight prose.

Alas, as I age, I find myself nearly agreeing with Ms Didion at times. Though some of the Haight ‘heads/hippies were decent peeps, many turned out to be as manipulative, conniving, and corporate as any GOP Nixonian. As with Bobby Weir hisself (not to say most of the phonies of Silicon Valley).

No feedback on the Dead vs Mothers/FZ Winterland showdown?? I think ’66 or ’67. According to some reports Zappa tried to help out ol Jerry, overweight, strung out, alcoholic. The JG Band opened for Zappa at times (with the ‘heads mostly hating the zappafreaks, and vice versa

LikeLike

Finally got a chance to sit down and read all six installments at once. Very good stuff. Very fun to read and well done.

LikeLike

Hi Chris — Well, as with all stories, there is never really “The End”…they keep going and going. I had to check with Peter to be sure, but I thought I recognized that house. Must have been shortly after you guys left, or maybe there was an overlap of residents, but it couldn’t have been later than 1964 that Peter van Gelder, George Hunter, Oscar Daniels, Riley and Marsha Turner and someone named Eurydice whom I can’t recall lived in that same house on Divisadero! Thank you for keeping the wheel turning! Leslie

LikeLike

My goodness, Leslie.� I’m glad you thought to ask Peter.� Those are all major A-list people from our past (I know that sounds snobby)� Even Eurydice (probably she took her name from the enormously popular film of the time, Black Orpheus.)� I wonder if she pronounced it “Oor-o-dees”.�

Oscar Daniels!� Man, I haven’t thought of him in a while.� I wonder if he is still alive.� And Riley’s ole lady Marcia.

Rochanah Weissinger on my Facepage page is Solveig from 311 Judah.� I remember her husband Jim (later changed his name to Reynold through Subud) was good friends with Oscar.� I might just give him a call, see what he remembers.�

That is fascinating information.� I will do something with it.� Thanks!

You okay?� You are so beautiful to me.

Chris

LikeLike

Thanks for the memories, dear hearts. You’ve made my day.

Alison

LikeLike

Alison Franks?

Alive and well, I hope!

I remember you vividly, and that you stayed at 857 Divisidero for a few days.

You are one of my best memories from Santa Barbara

Nathan zakheim

LikeLike

I’m finally replying, Nathan. I live in Albuquerque NM (22 years now), where currently I’m making necklaces from vintage buttons (see alisonfranksarts.blogspot.com). Married to Larry Sklar for near 37 yrs. now. One daughter, Annelise, is 34 and the ref. librarian for poli. sci, the data librarian, and asst. head of Gov. Info. Services at UC-San Diego. I still think your Julie is about 7, but I found a shot of her on the Internet and she’s not 7! I looked at Loren’s art online – terrific!

Best,

Alison

LikeLike